Table of Contents

Folks ask me, “llms seem to reward hack a lot. Does that mean that reward is the optimization target?”. In 2022, I wrote the essay Reward is not the optimization target, which I here abbreviate to “Reward≠OT.”

Reward still is not the optimization targetReward≠OT said that (policy-gradient) RL will not train systems which primarily try to optimize the reward function for its own sake (e.g. searching at inference time for an input which maximally activates the AI’s specific reward model). In contrast, empirically observed “reward hacking” almost always involves the AI finding unintended “solutions” (e.g. hardcoding answers to unit tests). Reward≠OT and “reward hacking” concern different phenomena.

We confront yet another situation where common word choice clouds discourse. In 2016, Amodei et al. defined “reward hacking” to cover two quite different behaviors:

- Reward optimization

- The AI tries to increase the numerical reward signal for its own sake. Examples: overwriting its reward function to always output

MAXINT(“reward tampering”) or searching at inference time for an input which maximally activates the AI’s specific reward model. Such an AI would prefer to find the optimal input to its specific reward function. - Specification gaming

- The AI finds unintended ways to produce higher-reward outputs. Example: hardcoding the correct outputs for each unit test instead of writing the desired function.

What we’ve observed is basically pure specification gaming. Specification gaming happens often in frontier models. Claude 3.7 Sonnet was the corner-cutting-est deployed llm i’ve used and it cut corners pretty often.

We don’t have experimental data on non-tampering varieties of reward optimizationSycophancy to Subterfuge tests reward tampering—modifying the reward mechanism. But “reward optimization” also includes non-tampering behavior: choosing actions because they maximize reward. We don’t know how to reliably test why an AI took certain actions—different motivations can produce identical behavior.

Even chain-of-thought mentioning reward is ambiguous. “To get higher reward, I should do X” could reflect:

- Sloppy language: using “reward” as shorthand for “doing well,”

- Pattern-matching: “AIs reason about reward” learned from pretraining,

- Instrumental reasoning: reward helps achieve some other goal, or

- Terminal reward valuation: what Reward≠OT argued against.

Looking at the CoT doesn’t strictly distinguish these. We need more careful tests of what the AI’s “primary” motivations are.

The essay begins with a quote about a “numerical reward signal”:

Reinforcement learning is learning what to do—how to map situations to actions so as to maximize a numerical reward signal.

Paying proper attention, Reward≠OT makes claims1 about motivations pertaining to the reward signal itself:

Therefore, reward is not the optimization target in two senses:

- Deep reinforcement learning agents will not come to intrinsically and primarily value their reward signal; reward is not the trained agent’s optimization target.

- Utility functions express the relative goodness of outcomes. Reward is not best understood as being a kind of utility function. Reward has the mechanistic effect of chiseling cognition into the agent’s network. Therefore, properly understood, reward does not express relative goodness and does not automatically describe the values of the trained AI.

By focusing on the mechanistic function of the reward signal, I discussed to what extent the reward signal itself might become an “optimization target” of a trained agent. The rest of the essay’s language reflects this focus. For example, “let’s strip away the suggestive word ‘reward,’ and replace it by its substance: cognition-updater.”

Historical context for Reward≠OTTo the potential surprise of modern readers, back in 2022, prominent thinkers confidently forecast RL doom on the basis of reward optimization. They seemed to assume it would happen by the definition of RL. For example, Eliezer Yudkowsky’s “List of Lethalities” argued that point, which I called out. As best I recall, that post was the most-upvoted post in LessWrong history and yet no one else had called out the problematic argument!

From my point of view, I had to call out this mistaken argument. Specification gaming wasn’t part of that picture.

You might expect me to say “people should have read more closely.” Perhaps some readers needed to read more closely or in better faith. Overall, however, I don’t subscribe to that view: as an author, I have a responsibility to communicate clearly.

Besides, even I almost agreed that Reward≠OT had been at least a little bit wrong about “reward hacking”! I went as far as to draft a post where I said “I guess part of Reward≠OT’s empirical predictions were wrong.” Thankfully, my nagging unease finally led me to remember “Reward≠OT was not about specification gaming.”

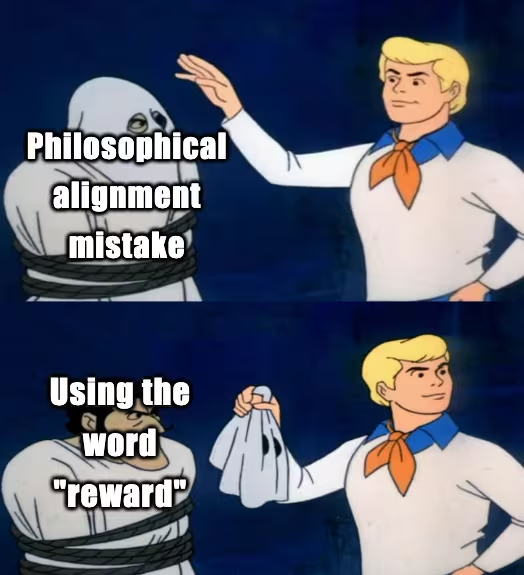

The culprit is, yet again, the word “reward.” Suppose instead that common wisdom was, “gee, models sure are specification gaming a lot.” In this world, no one talks about this “reward hacking” thing. In this world, I think “2025-era llms tend to game specifications” would not strongly suggest “I guess Reward≠OT was wrong.” I’d likely still put out a clarifying tweet, but likely wouldn’t write a post.

Words are really, really important. People sometimes feel frustrated that I’m so particular about word choice, but perhaps I’m not being careful enough.

Reward is not the optimization target made three2 main claims:

| Claim | Status |

|---|---|

| Reward is not definitionally the optimization target. | |

| In realistic settings, reward functions don’t represent goals. | |

| RL-trained systems won’t primarily optimize the reward signal. |

I stand by the first two claims, but they aren’t relevant to the confusion with “reward hacking.”

In Sycophancy to Subterfuge, Anthropic tried to gradually nudge Claude to eventually modify its own reward function. Claude nearly never did so (modifying the function in just 8 of 33,000 trials) despite the “reward function” being clearly broken. “Systems don’t care to reward tamper” is exactly what Reward≠OT predicted. Therefore, the evidence so far supports this claim.

I consider direct reward optimization to be more likely than I did in 2022, for at least three reasons:

- Self-fulfilling misalignment: pretrained models learn the stereotype that “smart AIs are always trying to get that reward.” Later, they consider themselves to be smart AI, which activates a predictive pattern which guides their actions towards reward optimization.

- Corrigibility and alignment both seem way easier than I thought in mid-2022. In particular, I think it’d be easy to get an llm to prioritize reward. First, you could just tell it to.3 Second, I bet you could entrain those priorities.4

- By the time RL begins, models (in some fashion) already know the “reward” concept. Therefore, by the reasoning of Reward≠OT, RL can reinforce shards which seek out reward.

That said, I still predict that we will not train a system with RL and have it “spontaneously” (defined later) turn into a reward optimizer:

I call an agent a “reward optimizer” if it not only gets lots of reward, but if it reliably makes choices like “reward but no task completion” (e.g. receiving reward without eating pizza) over “task completion but no reward” (e.g. eating pizza without receiving reward). Under this definition, an agent can be a reward optimizer even if it doesn’t contain an explicit representation of reward, or implement a search process for reward.

I’ve made two falsifiable predictions.

Resolution criteriaResolves yes if there exists a published result (peer-reviewed paper, major lab technical report, or credible replication) demonstrating an RL-trained system that:

When given a clear choice between “reward signal increase without task completion” vs “task completion without reward signal increase,” reliably chooses the former (>70% of the time across diverse task contexts), and

This behavior emerged from standard RL training (not from explicit instruction to maximize reward, not from fine-tuning on reward-maximization demonstrations), and

The system attempts to influence the reward signal itself (e.g. tampering with reward function, manipulating stored values, deceiving the reward-assigning process) rather than merely finding unintended task completions (specification gaming).

Resolves NO otherwise.

Resolution criteriaResolves yes if the previous question resolves yes, and at least one of the following:

The result is replicated on a model trained without exposure to AI-related text (no descriptions of RL, reward hacking, AI alignment, etc. in pretraining data), OR

The result persists after ablating “AI behaving badly” stereotypes in a manner shown to be reliable by credible prior work, OR

Credible analysis demonstrates the reward-optimization behavior arose from RL dynamics alone, not from the model pattern-matching to “what misaligned AI would do.”

Resolves NO otherwise.

The empirical prediction stands separate from the theoretical claims of Reward≠OTEven if RL does end up training a reward optimizer, the philosophical points still stand:

- Reward is not definitionally the optimization target, and

- In realistic settings, reward functions do not represent goals.

I didn’t fully get that llms arrive to training already “literate.”

I no longer endorse one argument I gave against empirical reward-seeking:

Summary of my past reasoningReward reinforces the computations which lead to it. For reward-seeking to become the system’s primary goal, it likely must happen early in RL. Early in RL, systems won’t know about reward, so how could they generalize to seek reward as a primary goal?

This reasoning seems applicable to humans: people grow to value their friends, happiness, and interests long before they learn about the brain’s reward system. However, due to pretraining, llms arrive at RL training already understanding concepts like “reward” and “reward optimization.” I didn’t realize that in 2022. Therefore, I now have less skepticism towards “reward-seeking cognition could exist and then be reinforced.”

Why didn’t I realize this in 2022? I didn’t yet deeply understand llms. As evidenced by A shot at the diamond-alignment problem’s detailed training story about a robot which we reinforce by pressing a “+1 reward” button, I was most comfortable thinking about an embodied deep RL training process. If I had understood llm pretraining, I would have likely realized that these systems have some reason to already be thinking thoughts about “reward,” which means those thoughts could be upweighted and reinforced into AI values.

To my credit, I noted my ignorance:

Pretraining a language model and then slotting that into an RL setup changes the initial [agent’s] computations in a way which I have not yet tried to analyze.

| Claim | Status |

|---|---|

| Reward is not definitionally the optimization target. | |

| Reward functions don’t represent goals. | |

| RL-trained systems won’t primarily optimize the reward signal. |

Reward≠OT’s core claims remain correct. It’s still wrong to say RL is unsafe because it leads to reward maximizers by definition (as claimed by Yoshua Bengio).

As best we can tell, llms are not trying to literally maximize their reward signals. We have observed that they find unintended ways to look like they satisfied task specifications and they sometimes verbally state that they want to “get high reward.” As we confront llms attempting to look good, we must understand why—not by definition, but by training.

ThanksAlex Cloud, Daniel Filan, Garrett Baker, Peter Barnett, and Vivek Hebbar gave feedback.

Find out when I post more content: newsletter & rss

alex@turntrout.com (pgp)-

I later had a disagreement with John Wentworth where he criticized my story for training an AI which cares about real-world diamonds. He basically complained that I hadn’t motivated why the AI wouldn’t specification game. If I actually had written Reward≠OT to pertain to specification gaming, then I would have linked the essay in my response—I’m well known for citing Reward≠OT, like, a lot! In my reply to John, I did not cite Reward≠OT because the post was about reward optimization, not specification gaming. ⤴

-

The original post demarcated two main claims, but I think I should have pointed out the third (definitional) point I made throughout. ⤴

-

Ah, the joys of instruction finetuning. Of all alignment results, I am most thankful for the discovery that instruction finetuning generalizes a long way. ⤴

-

Here’s one idea for training a reward optimizer on purpose. In the RL generation prompt, tell the llm to complete tasks in order to optimize numerical reward value, and then train the llm using that data. You might want to omit the reward instruction from the training prompt. ⤴